Going on two random football data exploration trips

Two interesting rabbit holes, two unfinished articles, and why having random data analysis ideas are fun!

While I am quietly doing my reflection of this year in an attempt to find a different approach to make the process of working on football projects more fun and honest for myself, I stumbled across two unfinished articles about two data rabbit holes that I thought were quite interesting to me. Those ideas are still fascinating to dive deeper into, but even though I have gone to the extent to gather data and create a visualisation for it, those ideas just did not have enough ground to make up a solid article without me going on a ramble episode.

So, as a potentially final article for 2025 and as an early holiday gift, I have condensed both articles into two bite-size articles that still covers the visualisation that I have made while also not too long to feel like me rambling too much. Hope you will enjoy these very random, data-focused rabbit holes!

The curious case of Bundesliga teams and European football

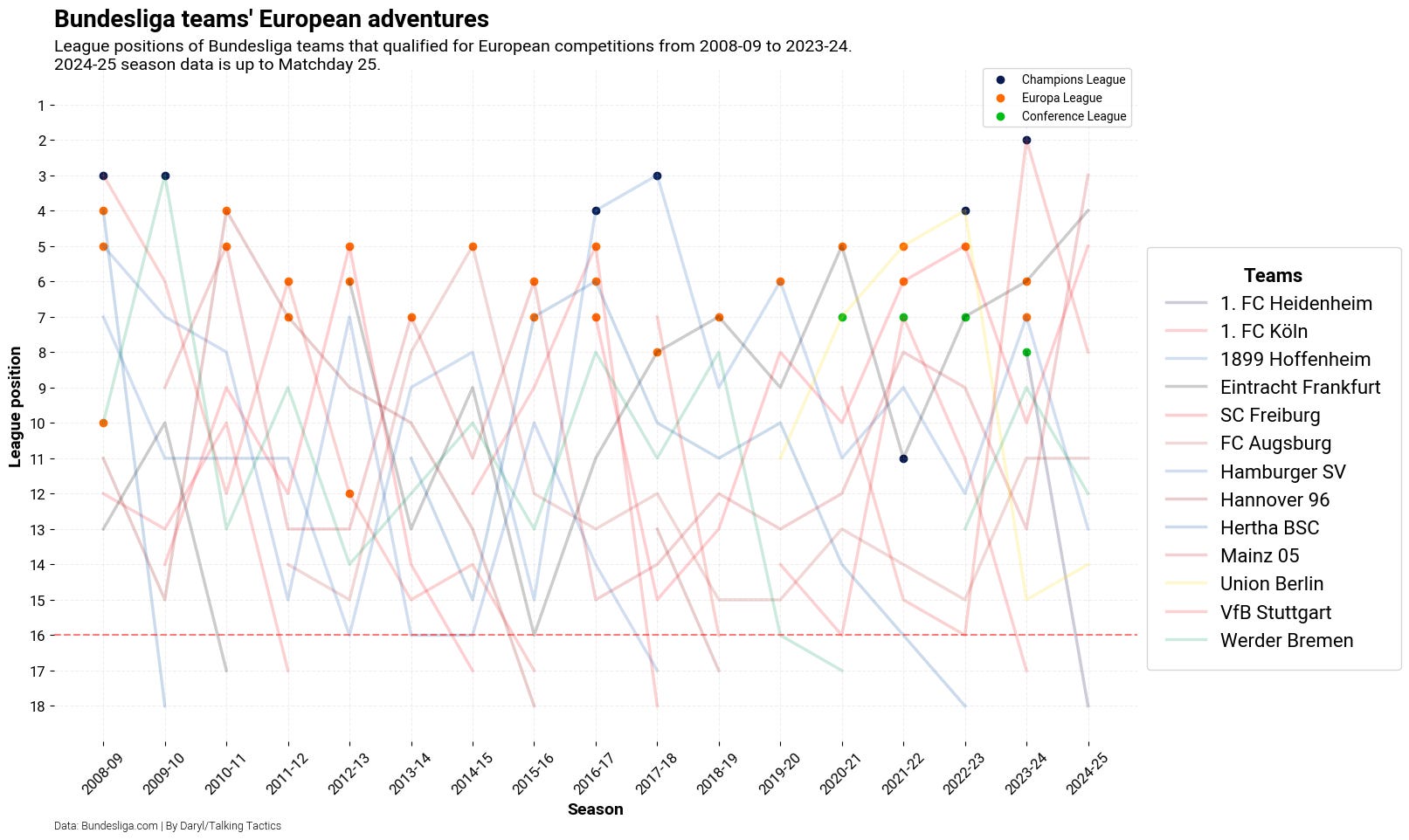

In the past few seasons, there have been many Bundesliga teams who have not achieved the same height after playing in Europe. Without counting top teams like Bayern München, Borussia Dortmund, Leipzig, or Bayer Leverkusen, and teams who were somewhat consistent in Europe in the past like Borussia Mönchengladbach, Schalke 04, and VfL Wolfsburg, there are more than a handful of Bundesliga teams who have dropped off quite significantly after experiencing the height of playing continental football. The fluctuation in league position for the aforementioned teams, mostly for Dortmund nowadays, are either due to inefficient recruitment, managerial inconsistency, or off-field shenanigans. As such, I will only be looking at the remaining teams in the league, their European adventures, and the aftermath of those adventures.

Quick housekeeping

I will also only be examining from the 2009/10 season afterwards, which was when the UEFA Cup was reformed into the Europa League as we now know and familiar with. I am not that familiar with the UEFA Cup, and also with the complication of the Intertoto Cup, there are just too many variables that need to be taken into account. So I will be sticking to what I know, which is the current Europa League, the recently-formed Conference League, and the Champions League for some teams. Okay, with the housekeeping stuff out of the way, let’s get into the data!

What does the data highlight?

If there is only one example of a Bundesliga team who played in Europe then significantly dropped off in the seasons afterwards, then I will say it was that team’s problem of not managing or distributing the European money well to benefit the club. If there are two examples of such situation, then I will say both teams were in a similar situation. If there are three examples, then okay, there might be a correlation here…If there are four examples, then there is definitely something that is happening with German teams after playing in Europe. If there are more examples, then the problem is actually very real!

Three teams that easily come to mind that have experienced that “symptom” are Union Berlin and Heidenheim. With Union Berlin, their rise to the top of the Bundesliga since their promotion in the 2019/20 season had been steady and solid. Under Urs Fischer, they qualified for the Conference League, then moved up to the Europa League, and eventually reached the Champions League. But it was that season in the UCL that Union started to experience their downward trajectory, which left them 15th on the league table after the conclusion of the 2023/24 season, 13th at the end of the 2024/25 season, and currently 11th after 12 matches of the 2025/26 season as they slowly bounce back.

Heidenheim are also experiencing a similar symptom. Their rise from the Regionalliga to the Bundesliga under Frank Schmidt was nothing short of a magical run, and they capped it off with a Conference League spot for the 2024/25 season. Yet they only barely survived last season after finished in 16th and after beaten SV Elversberg in the promotion/relegation playoff, and after 12 matches of the 2025/26 season, they currently sit 16th once more with just 8 points to their name.

After recovering from a dreadful start to the 2024/25 season under Bo Svensson, Mainz 05 and Bo Henriksen finished last season in 6th place, which earned them a spot in the Conference League this season. But their fortunes have completely flipped this season as Mainz are finding themselves bottom of the Bundesliga table with two points less than Heidenheim’s current tally and a single win after 12 matches. They are the three most recent examples of Bundesliga teams who played in Europe then struggled in the league afterwards, but there have been a few more:

As the title image suggested, 1.FC Köln’s 2017/18 season, where they played in the Europa League and finished last in the Bundesliga in the same season. They actually suffered the symptom again in 2022/23, where they finished 11th in the same season they played in Europe and got relegated in the season afterwards.

VfL Wolfsburg qualified for the 2015/16 Champions League group stage, and while they managed to finish 8th in the same season, they finished 16th in the two season afterwards and survived two playoff wins to retain their Bundesliga status. They bounced back and made their return to the Europa League first in the 2019/20 and 2020/21 seasons, then back to the UCL group stage in the 2021/22 season, but Die Wölfe have since returned to a downward trajectory.

This (2025/26) season was not the first time that Mainz 05 got the symptom, having encountered it twice after they played in the Europa League in 2011/12 then finished 13th in the same season, and in 2016/17 where they finished 15th.

SC Freiburg also got the symptom twice in the 2013/14 season, where they also played in the Europa League and finished 14th in the same season, only to be relegated next season, and the 2017/18 season where they finished 15th, three points off of Wolfsburg’s 16th place.

Eintracht Frankfurt experienced the same symptom in the similar timeframe as Freiburg, they finished in 13th in the 2013/14 season and recovered relatively quickly to finished 9th in the 2014/15 season, but they then finished 16th in 2015/16 and only survived by winning the promotion/relegation playoff match.

Of these examples that I have listed, only Freiburg and Frankfurt have managed to stabilise themselves and got themselves to a position where they are constantly competing for and securing a European spot every season afterwards. Both clubs have used the revenue from playing in Europe well to reinvest back into their squad with slightly different recruitment strategies, which have turned that inconsistent revenue stream from UEFA to a consistent stream, thus providing a solid foundation for both Freiburg and Frankfurt to be competitive every year.

Some of the successful recruitment strategies that both Freiburg and Frankfurt have applied includes:

Buying undervalued players from domestic rivals for a fairly low price tag, with examples like:

Maximillian Eggestein, Michael Gregoritsch, Eren Dinkci, Patrick Osterhage, Igor Matanovic for Freiburg

Michael Zetterer, Jonathan Burkardt, Ansgar Knauff, Can Uzun, Nathaniel Brown for Frankfurt

Buying underperformed strikers and provide a platform for them to show their ability, with examples like:

Sebastian Haller, Luka Jovic, Ante Rebic, Andre Silva, Randal Kolo Muani, Hugo Ekitike, Omar Marmoush for Frankfurt

Invest in undervalued talents from other European leagues, with examples like:

Willian Pacho, Hugo Larsson, Jean-Matteo Bahoya, Kaua Santos, Oscar Hojlund for Frankfurt

What can we learn here?

The lesson is, sometimes, playing in Europe actually do more harm than good to a team. When a team participate in the UEFA Cup, Europa League, or now, the Conference League, the spotlight is on that team as they try to put on a magical performance that will put them into the history books. But, once that spotlight is gone, not many people actually follow up on that team to see if they are still kicking around, if not thriving, or are they feeling the effect of that European season and are currently struggling.

Bundesliga clubs are at a better financial position than some Eastern European clubs who have completely disappeared after a season or two in Europe, but that does not mean some Bundesliga clubs are not affected by that problem. One of the main reasons is plainly because clubs tend to overinvest into the playing squad for a single season, which leaves them in a worse financial position when European football is not on their calendar. Another reason is clubs do not redistribute and reinvest the revenue that comes from UEFA very well, thus that revenue cannot continue to sustain the club and generate future revenue for the club to keep them competitive.

It is not all doom and gloom, however, as Freiburg and Frankfurt have shown. There are definitely lessons to be learned from both teams on how to reinvest the revenue from playing in Europe into a revenue stream that can sustain the club long-term. Whether it is from smart recruitment strategies or off-the-pitch revenue streams, there are always rooms for clubs to improve on their financial decisions.

Why does this season’s AFC Champions League Two feels different?

Speaking of recruitment, if you have been following the AFC Champions League Two this season, you might notice something a bit different than previous seasons.

Asian clubs’ lineups back in the days were definitely not flooded with foreign players when the foreign players cap was still in place. Before 2022, all clubs from the East and West could only register 4 foreign players for the AFC competitions, three non-AFC players and one player from any other AFC members. Since 2022, the AFC have loosened the cap bit by bit, going from being able to register any amount of foreign players but clubs could only fielded 3+1 players in 2022 and 5+1 in 2023-24, to completely remove the cap when the competition was reformed and split into the AFC Champions League Elite and the AFC Champions League Two that we now know. Interestingly, these changes coincide with the heavy investment in star players by the Middle East clubs, but it’s probably just a coincidence…right?

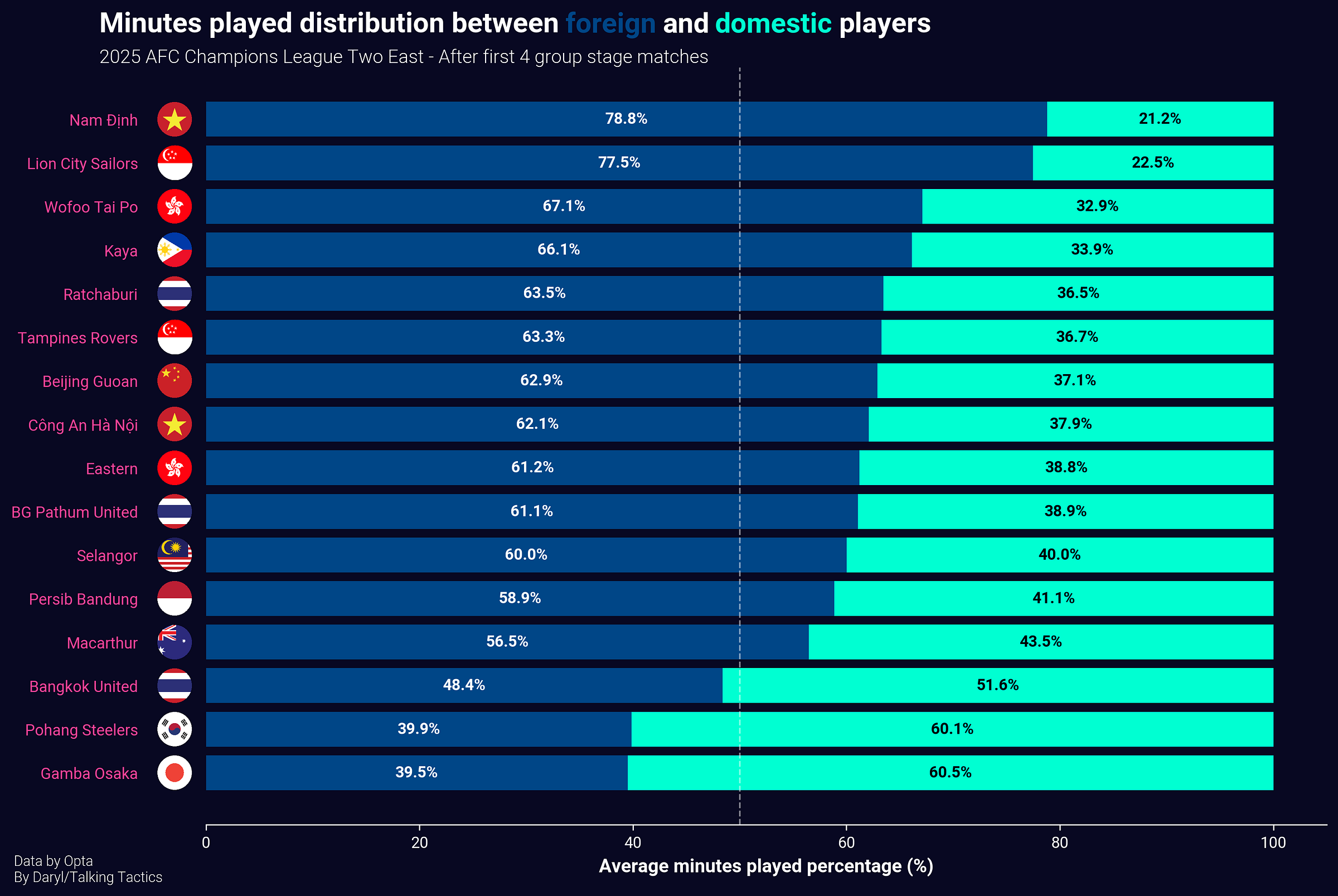

While the lineup of Western Asian clubs look ever closer to a club who regularly plays in the UEFA Champions League thanks to those ‘timely’ changes from the AFC, the Eastern Asian clubs have also capitalised on those changes to bolster their lineup with major signings before this season started. Vietnam’s Nam Dinh and Singapore’s Lion City Sailors are just two clubs who have taken things to the extreme, but other Southeast Asian clubs have also spent big to bring in their own foreign signings.

Obviously there are two sides to this argument. On one side, bringing high quality foreign players into the club will help the development of local talents as they are able to train and receive mentoring from the foreign players. It is not a usual occurrence that Vietnamese players get to play and train alongside Ajax Amsterdam academy graduate and former Norwich City full-back Mitchell Dijks or former Brighton & Hove Albion striker Percy Tau, right?

However, on the opposite side, and the side that I am on, I start to question the sustainability of such approach and whether this is actually a good long-term thing for the club. There are so many questions surrounding the risk of bringing so many players in for a very short period of time. But before that,…what does the data say?

What does the data highlight?

While Eastern Asian clubs have always relied on the quality of foreign players in past Champions League seasons, this year has seen an unprecedented rise, with both Nam Dinh and Lion City Sailors leading the way in average minutes played percentage by foreign players. The two aforementioned clubs are somewhat outliers as foreign players took up more than 70% of their average minutes played, but the average for most Eastern Asian clubs is still on the high end, around 63%.

For clubs at the lower end like Pohang Steelers and Gamba Osaka, it’s easy to explain why their minutes played share by foreign players is significantly lower than the rest of the East. Japanese and South Korean clubs have never had to rely very heavily on foreign players to achieve good results in the Champions League because their domestic players are more than good enough to help them advance beyond the quarter-final. You do not have to look any further for an example as Kawasaki Frontale only used two foreign players in Erison and Marcinho during the knockout stages and on their way to the Champions League Elite final last season. Technically, they also had goalkeeper Jung Sung-ryong, who did not play any knockout matches, centre-back Cesar Haydar and striker Patrick Verhon, who both only played in two group stage matches each. Even though Macarthur’s foreign players have played more than 50% of their average minutes in the Champions League Two, they do not have as many foreign players as other Southeast Asian clubs due to them having to comply with the A-League Men’s foreign player cap and limited resources available to Australian clubs.

For the rest of the East, this highlights a fairly significant problem where clubs who do not have a strong domestic core have to rely heavily on the quality of the foreign players that they recruit. This problem has always been there for most Eastern Asian clubs, but with the cap now completely removed by the AFC and no financial regulations in place, clubs can theoretically recruit an unlimited number of foreign players as long as their finance allows. While this can increase the level of competitiveness for the competition, I think this will do more harm than good to the clubs.

What are some of the risks for East Asian clubs?

The obvious risk of this approach is to the club’s finance. The ability to recruit and field an unlimited number of foreign players will definitely encourage clubs to spend beyond their financial capability, which for most clubs can bring long-term consequences if they do not maintain their spot in the Champions League. For clubs who have strong financial backing like Lion City Sailors, the damage will be slightly less substantial and harder to spot. However, for clubs like Nam Dinh or Kaya-Iloilo, overspend what they are capable of is a one-way ticket to the realm of bankruptcy.

For example, it is fairly unlikely that players who have made a name for themselves in Europe and Brazil and are still somewhat in their prime like Mitchell Dijks, Percy Tau, Arnaud Lusamba, or Chadrac Akolo would take a significant paycut to join a Vietnamese club. As such, their salaries are likely to be one of the highest, if not the highest, that a Vietnamese club have ever paid a foreign player. Even worse, the contracts that are given out to these players are likely to be 1-year long to only cover the Champions League Two campaign, which means there is no possibility of selling these players to potentially recoup some of the salary paid, so most of their very high salaries are almost certainly a loss to the club.

Another risk is loss of club identity. This is a debatable one as there are always two sides to this argument, one set of fans (mostly Asian fans) prefer clubs to prioritise short-term wins by bringing in the best players possible; the other, smaller set of fans might worry a bit about whether the players who are representing their club are actually playing for the shirt. For me, if you are one of the clubs who represent your country at a continental level, it is more important to trust the local players who understand what it means to play for the club and push themselves against better players. In the end, the local players are somewhat an extent of the fans, there is nothing better than seeing a player who have grown up in the surrounding areas, went through the club’s youth level, to playing for the club at a continental level, which allows the fans to buy into the club and support the club even more.

Not last, not least (but I don’t want to make this article very long), is the risk that this approach poses to domestic players. As clubs prioritise short-term results over the development of local players, their minutes get restricted and hinders their development, which also makes the national team worse because most of a nation’s best players should be playing at the continental level. I think either Herve Renard or Roberto Mancini have spoken up about this problem when more foreign players are taking over the Saudi Pro League, leaving local Saudi Arabian players with less and less minutes played and weaken the player pool selection for the national team as a result. It has already happened across a few East Asian national teams, which is one of the main reasons that drives a massive boom in naturalisation for Southeast Asian nations, and it is only going to get worse if things do not change.

What can we learn here?

The lession is, once again, overinvesting into the playing squad and foreign-players-leaned recruitment approach are not usually the way to go if a club want to become sustainable in the long run. This is not a significant problem in European football because there is at least an intention to focus on the long-term and not trying to run the club into the ground. But, in most cases, Asian clubs prefer to think short-term and that never ends up very well for their fortune.

Finding a healthy balance between foreign and domestic players contribution is not easy and I have not seen a club outside of Japan or South Korea who have done that very well. With football analytics being mostly geared towards Europe and the Americas, I definitely think this is a niche area where having more data can be extremely helpful because recruitment models and strategies that work for European and American clubs might not work very well for Asian clubs. The same goes for any kind of data-driven processes because of how different football is being run in Asia besides from having the ball on a pitch and 22 players try to chase after it.

But, until then, there are a lot left to be desired about how Asian clubs are being run. The AFC definitely will not change the regulations anytime soon, at least not until the Saudi boom dies down a fair bit, which means East Asian clubs can freely spend the money that they do not have on players who are most likely not going to bring any monetary values back to those clubs. If lucky, the recruited foreign players might turn out to be a solid player and can bring values on the pitch, which will soften the blow a bit, but will definitely not slow down the downward trajectory that can lead to something fairly significant in the future. Something like a relegation from the top division or outright bankruptcy are not off the table.