An overall review of the 2026 U23 Asian Cup group stage

Nobody asks for this, but what can we learn from all teams in the group stage?

With the current iteration of the U23 Asian Cup heading into the knockout phase, the best teams have showcased their strengths while a few upsets have happened here and there. But while the attention of most people will immediately turn to the upcoming quarter-final clashes, I want to stay with the group stage for a bit and actually review what happened over the past fairly chaotic week.

I think the group stage of any tournament is usually where teams show the best of their ability and play the style of football that they want to play. Obviously elimination was still on the line, but the stake was definitely lower than the upcoming quarter-final and there were reasons for teams to push themselves in order to hopefully secure a surprise qualification to the knockout phase. I won’t be surprised if a few teams will start to take on a more defensive mentality because it’s knockout football and if there’s a chance to cause an upset, teams will take it. This also means teams won’t play to their true ability, which can be hard to identify good players or interesting tactical points.

So, which interesting tactical trends can we learn from the group stage?

4-4-2 defensive block is the new norm

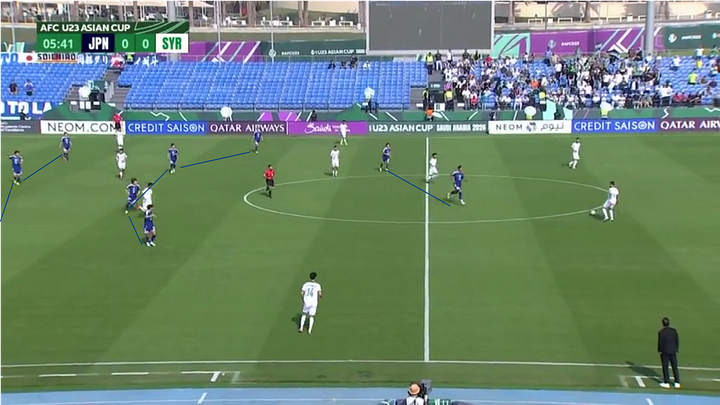

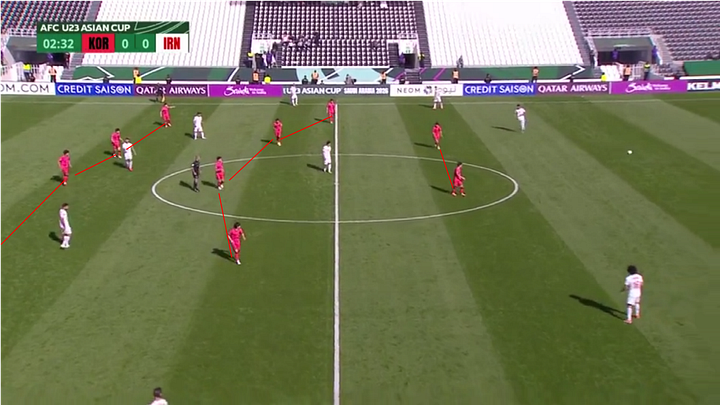

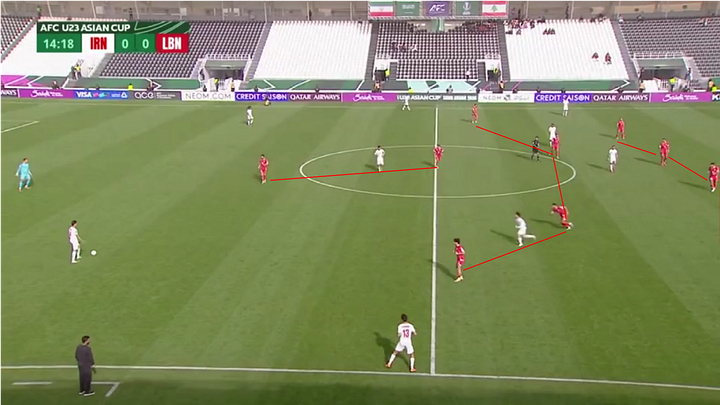

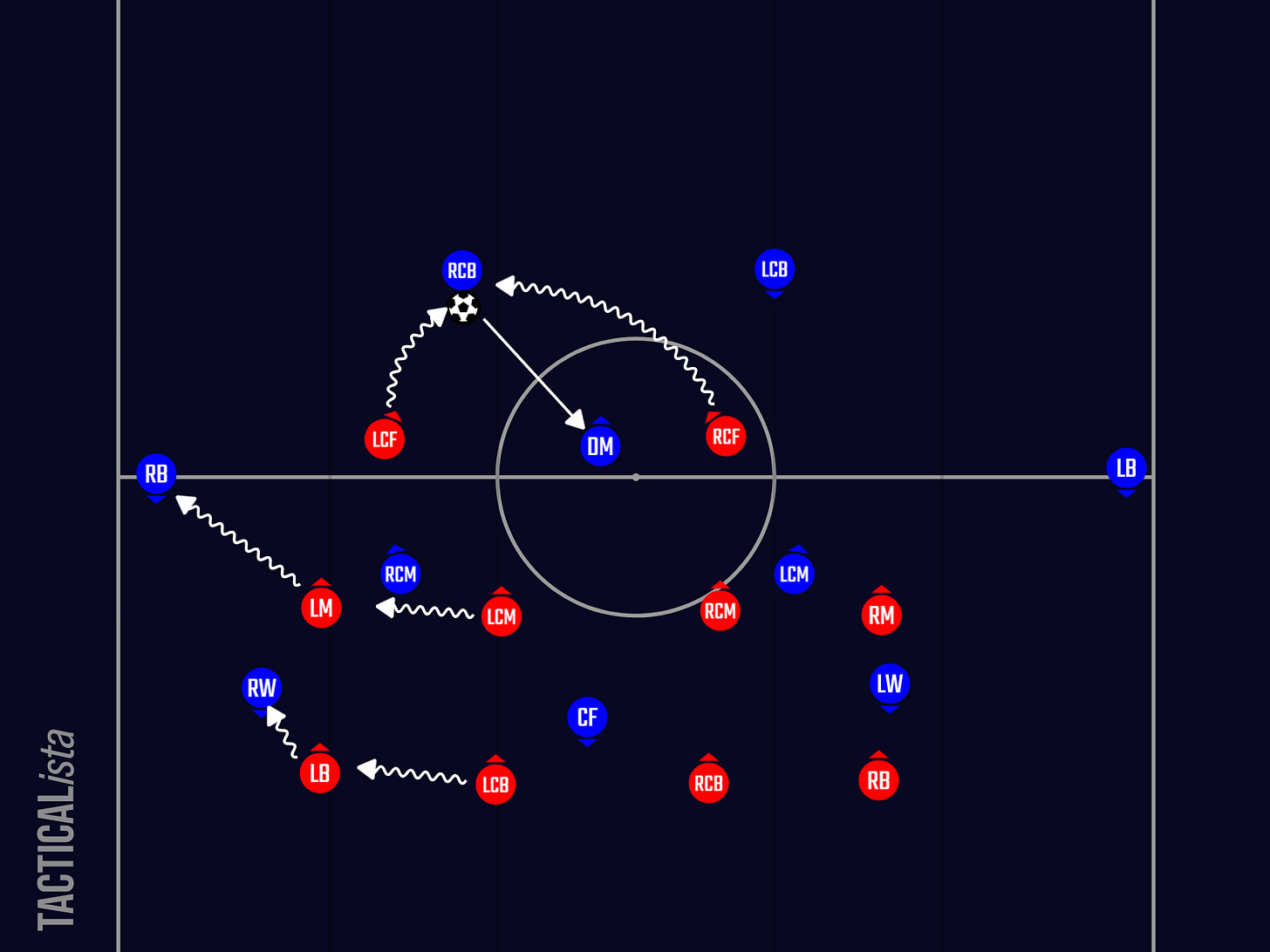

Personally, I think the fact that a lot of teams during the group stage adopted the 4-4-2 as their out-of-possession mid block or low block is a decent reflection of Asian coaching standard, in a good way of course, since Asian coaches are following what plenty of top European teams are doing. From top teams who adopted it like Japan and South Korea to underdogs like Kyrgyzstan and Lebanon, the 4-4-2 defensive block became a very common sighting during the group stage.

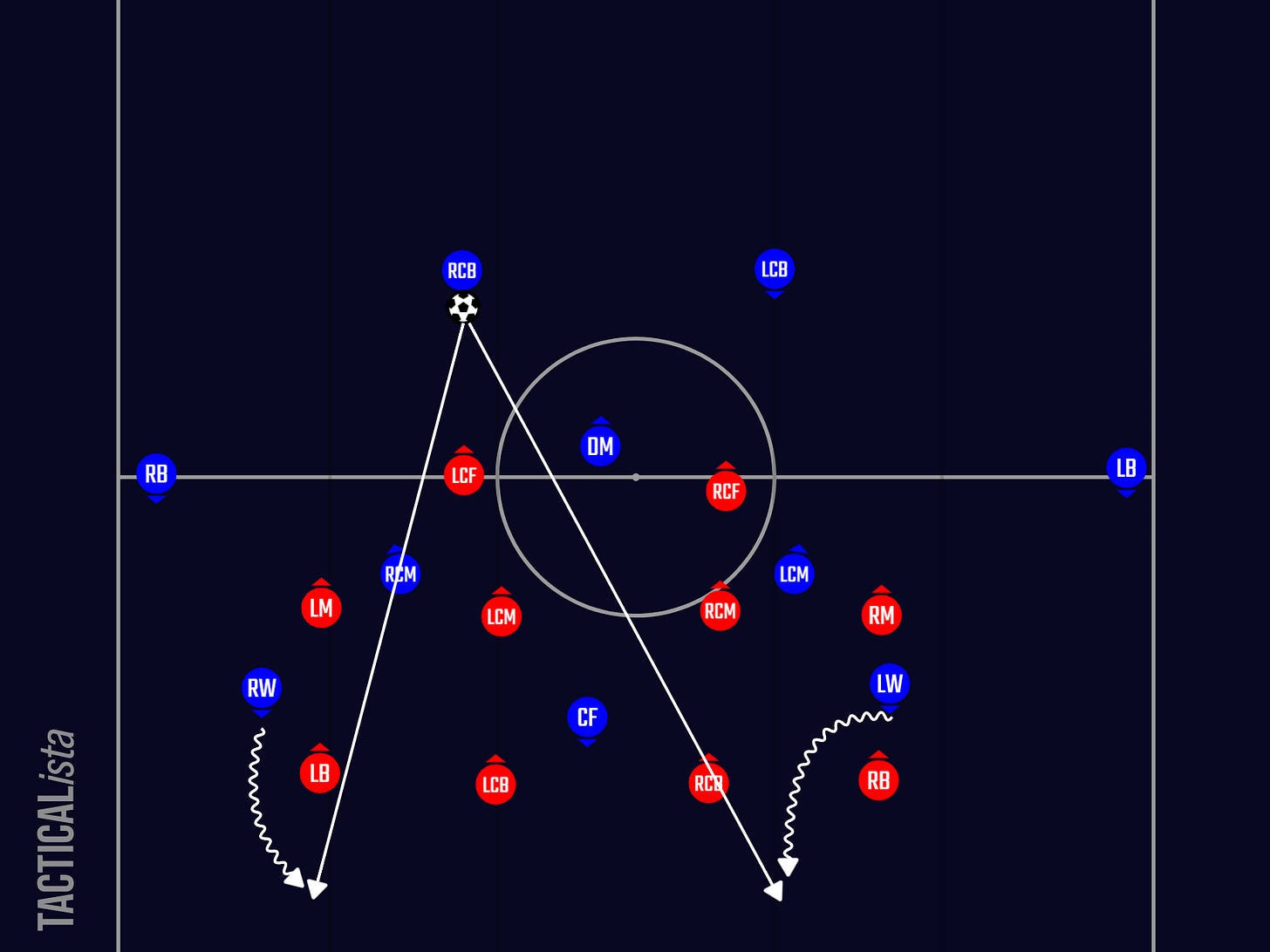

That’s not to say that all teams defend like everyone else in the competition because each team added their own touches to the traditional 4-4-2 block. But the core principles were there: preventing teams from attack down the middle and through the block, guiding the opposition out wide with the aim of creating overloads to regain possession, and attempting to disrupt the opposition’s build-up phase with two strikers. The 4-4-2 is just the perfect fit for these defensive approaches because it has two wide players who can stay in their positions to block wide attacks while also allowing the central midfielders and centre-backs to shift across and provide numerical advantage. It also has two strikers up front, which allows for the closing down of the opposition’s centre-backs and, if done right, blocking their passing options to either flanks using curved pressing runs, which forces them to pass into the block instead.

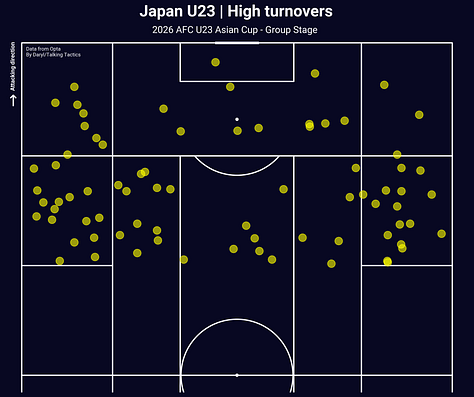

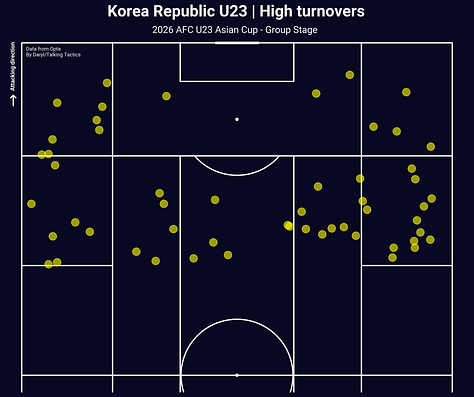

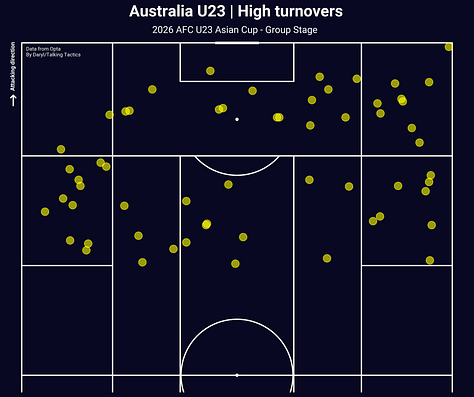

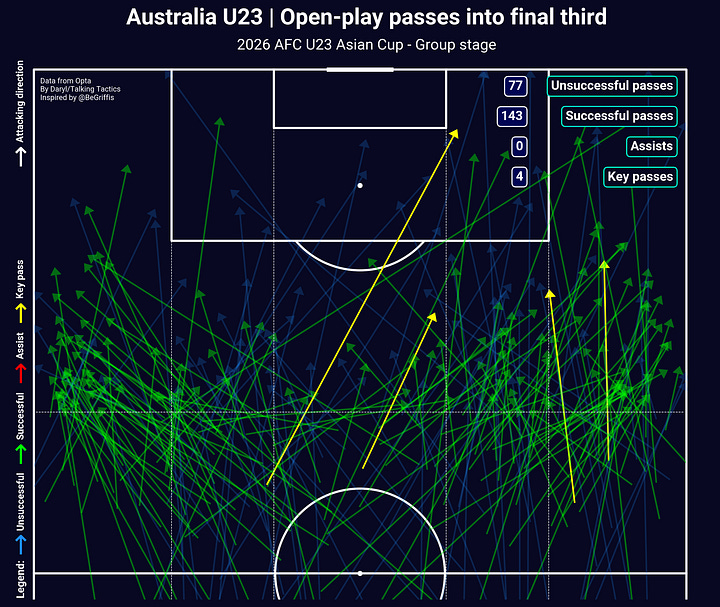

But where teams added their own touches lied in what they decided to do when they didn’t have the ball and how they approached it. For the favourites like Japan, South Korea or Australia, their 4-4-2 defensive block also became a part of their high press as they attempted to regain possession right inside of the opposition’s half and, sometimes, defensive third and generated high turnovers for a quick counter-attack. While also utilising the strengths of the 4-4-2, teams also tried to deploy a man-to-man press and targeted the opposition’s weak links to aggressively win the ball back or guided the ball wide as usual.

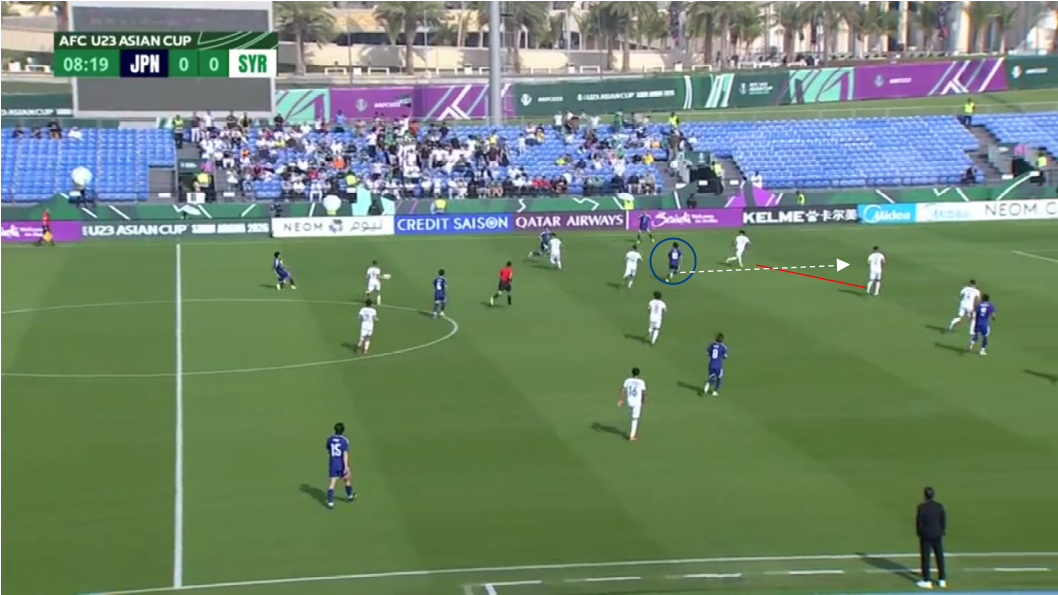

Some teams have had successes with generating high turnovers that eventually ended up as dangerous attacks, including South Korea themselves when they played Iran, or Japan when they met Syria and Qatar. But for others, their level of success stopped at ‘meh’. In fact, because teams tended to over-commit players for their press, their last defensive line was left vulnerable on various occasions due to different reasons.

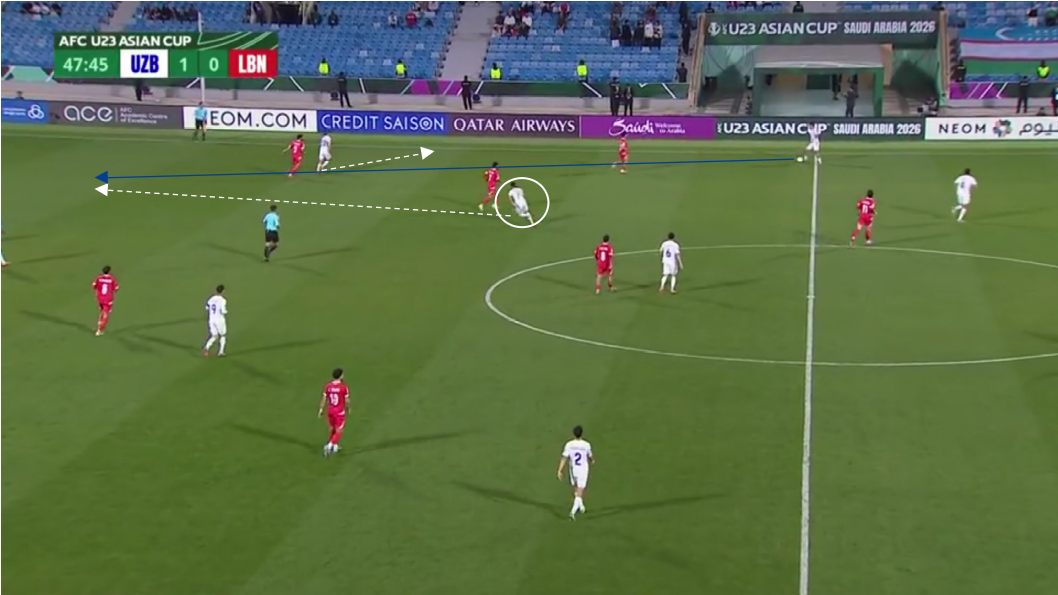

At times, the opposition had a bit of luck when playing through the press and left the pressing team’s midfielders with little to no time to retreat and support the defenders. This was more dangerous when the opposition had fast attackers who could dribble and get past defenders easily, or a combination of good and quick movements from the opposition’s players, which Uzbekistan demonstrated against Lebanon or even Thailand when they played Australia (even when they were down to 10-men).

Another way where the 4-4-2 high press was hurt was through long passes over the top to encourage attackers to run in behind. This also created a lot of damage for the 4-4-2 mid-block, which most teams also adopted as part of their defensive approach. With teams preferred to have at least three attackers up front, they usually exploited runs into the channels or runs on the outside shoulder of the defenders to receive the long ball in behind. This forced the defensive line to retreat closer to their own goal and stretched the defensive block if the midfielders also did not move back in time, which left a very dangerous gap where creative players could easily exploit.

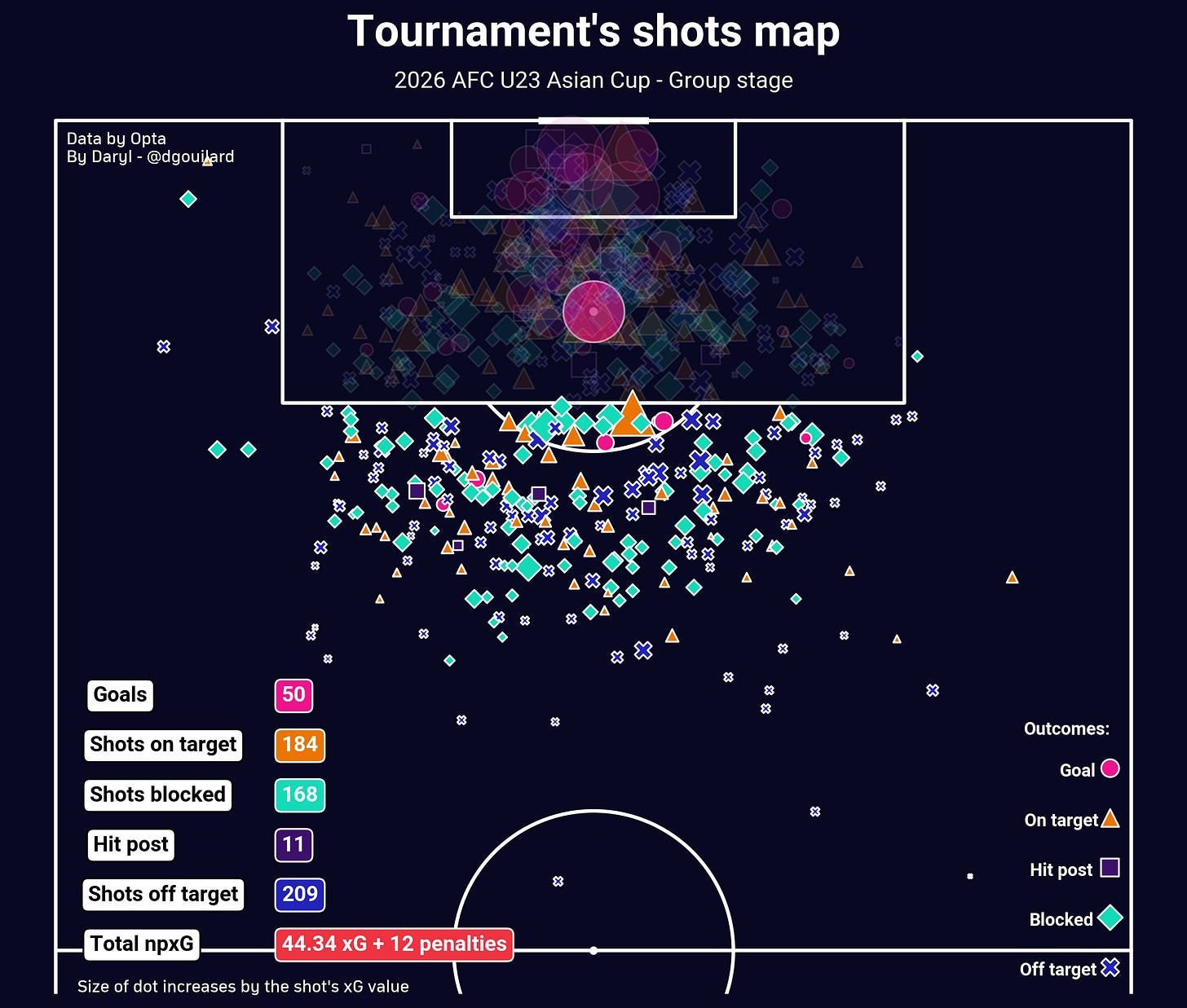

Most teams chose to get their most technical players into that gap and let them did what they were good at. Some chose to work their way into the box via their own technical ability or by working with their teammates, but some also chose to shoot right when they had the opportunity. This explained the fairly high volume of shots coming from outside of the box, which might have also contributed to the fairly average goal per match tally of 2.125 throughout the group stage.

Asia still have a #9 pandemic

One particular reason for why teams opted to use more long shots is simply because Asian teams still cannot produce an actual out-and-out striker. Someone who is more than just a poacher who is quick when he doesn’t have the ball and only look to crash into the box when a low cross or a cutback comes in. Someone who can actually provide a height advantage for more technical players like wingers or attacking midfielders to target with their floating crosses. And particularly, someone who has a good positioning sense to be at the right position and at the right time to pick up the ball and score 7 or 8 times out of 10.

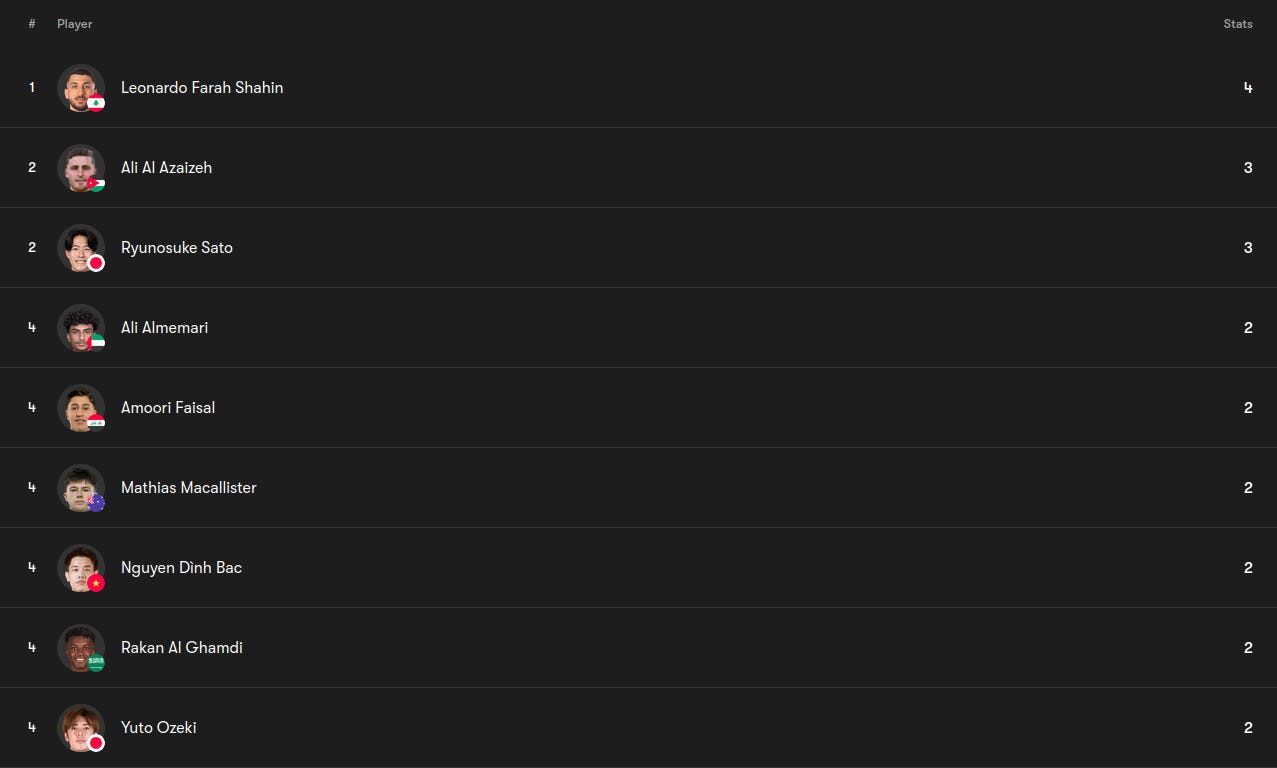

One look at the current top scorer chart and you will notice the lack of an actual #9 who scored more than 1 goal in the group stage. Only Vietnam’s Nguyễn Đình Bắc, UAE’s Ali Almemari and Iraq’s Amoori Faisal were used as a striker for their respective team, and they all are hybrids between a winger and a striker, not actual #9s. In fact, most of the players who scored more than two goals are either natural attacking midfielders or wingers.

This is in no part any team’s fault and it is not anybody’s fault. It is just the nature of how Asians are because it is rare to find an actual Asian who is tall and has good physicality to play as a focal point up front, probably rarer on the Eastern part of the continent. At the national team level, South Korea’s Cho Gue-sung is probably the best current example for someone who fits the description that I laid out above.

That said, a couple of teams have brought and experimented with the out-and-out #9 profile, but with little to no avail. Nigerian-Japanese striker Brian Seo Nwadike looked fairly out of depth in his first two matches for Japan’s U23 side as he struggled to link up with teammates around him. It is hard to blame him, though, since he is still playing at Japan’s university level while players like Ryunosuke Sato, Yuto Ozeki, or Yumeki Yokoyama are already getting regular minutes for J1 and J2 teams. French-UAE striker Junior Ndiaye has had a fair share of first team experience with Montpellier this season, but he also could not make much impact in the group stage and only managed to score 1 goal.

But every problem disguises itself as a challenge and if you view it from a different perspective, it is also an opportunity, as Japan showcased throughout the group stage and how Uzbekistan went 3-0 up against Lebanon after 60 minutes played. Both teams did not rely on their striker up front to provide the goals, but rather preferred to attack down the wings and put the ball at the feet of their most technical players, which were usually also their best players. While letting them did what they did best with the ball, other teammates around them also provided plenty of support.

That was how Japan’s Ryunosuke Sato and Yuto Ozeki ended up with 3 and 2 goals respectively. Japan usually preferred to attack with wingers like Yumeki Yokoyama, Haruta Kume, Shunsuke Furuya stretched the opposition’s defensive line by staying and receiving the ball wide, and their striker Nwadike held up the ball in the middle. This created spaces inside the half-spaces and also created channels for both Sato and Ozeki to frequently make runs into those areas and receive the ball from their teammate while they were also in good goal-scoring positions.

Uzbekistan also solved the problem in a fairly similar approach, but with a small twist. While still attacking down the wings and using their wingers and midfielders to the fullest, they also created spaces for plenty of off-ball runs and third-man runs to happen by constantly moving the ball side to side and dragging opposition players out of their natural positions. It allowed players like midfielder Sardorbek Bakhromov or winger Asilbek Jumayev to receive the ball in advantageous positions where they could continue to progress deep into the final third.

Is wing attack the most optimal solution?

But, amidst all of those innovative approaches, a question still lingers. Is wing attack the most optimal solution for Asian teams?

Throughout the group stage, that seemed to be the most popular attacking trend with so many teams attempted to enter the final third down both flanks. Crosses also became a somewhat common sighting in the group stage, especially when the opposition had managed to regroup and overloaded their own defensive third. At that point, crosses became the only way out for the attacking team as they were swung into the box as a hit-and-hope solution.

But without an actual #9 inside of the box, those crosses were largely ineffective and only served as an opportunity for the opposition to launch a quick counter-attack. Long shots from wide areas is not a sustainable option either. While one player might get lucky once or twice, it is hard to expect even the most technical player to replicate that long shot all the time, especially when the level of opposition analysis is getting more and more detailed, thus teams will be able to find solutions to limit those long shots sooner or later.

So…what now?

Japan and Uzbekistan have probably demonstrated a potential path moving forward, which is using tactics designed to bring the best out of each team’s best players, which are usually the midfielders or wide players like the wingers or the full-backs. While it is still relying on the core idea of attacking down both wings, these tactics also introduce the use of half-spaces and channels to get the ball into the box in a more effective way. Both teams also did not rely heavily on crosses, instead used plenty of movements and rotations to get their players into more advantageous positions to receive the ball.

While this approach requires high-quality coaching and a coaching staff who can get their players to buy into the ideas in a fairly short timeframe, it’s not impossible. The downside of this tactic is that it can be fairly hard to execute against a 5-man defensive line, where the opposition would most likely have a man advantage on most occasions. Once again, Japan have shown that it can be done against the UAE in the group stage, but it is also hard to compare Japan to anyone else since the quality of their players is very high.

Wing attacks are probably not going anywhere soon and might be more effective at the first team level where having naturalised strikers can be a significant game changer. But at youth levels like the U23 and below where most teams don’t have an actual #9 to lead the line, it becomes an interesting challenge for coaches to find other ways to generate goals and get their best players into good goal-scoring positions. This tournament is also a good opportunity for coaches to experiment with new ideas in an average stake environment and maybe, just maybe, interesting ideas can be found in a niche tournament that not many people pay attention to.

That leads perfectly into the next question…

Does the U23 Asian Cup need to happen every 2 years?

Now, to something different!

One thing that I noticed when I looked at the squads that teams brought to this tournament, which is the age of the players getting called up for this tournament is getting younger. My assumption immediately got validated when I checked Transfermarkt and realised that only the UAE and Lebanon’s squad average age is 22 and above.

While this can be because some teams do not bring their best talents to this tournament like Japan or South Korea, it also highlights a trend that is happening not just in Asia, but also across the world. In the past few years, teams have valued young players higher than ever before and gave them the opportunity to break through into the first team a lot earlier than before. Plenty of household names nowadays are still under 21 as many European teams continue to search all corners of the world for promising, young talents. Two famous alumnis of the U23 Asian Cup’s past few iterations are Manchester City and Uzbekistan’s Abdukodir Khusanov and Tottenham Hotspur and Japan’s Kōta Takai, both would technically still meet the requirements to be called up for this year’s tournament.

That begs the question, does the U23 Asian Cup actually need to be a biennial tournament anymore when this tournament only serves as Asia’s official qualification method for the Summer Olympics?

In the past, it made sense for the tournament to happen every 2 years as it opened up the window for scouts to look for the latest Asian talents coming through the pipeline. But many top teams are now seeing Asia as a serious talent factory, which means scouts and analysts are identifying young Asian talents way before they can even be called up for this tournament. Japan’s Rento Takaoka is a good example as he is already playing in Europe with Southampton and Valenciennes.

It does not make sense to change this tournament to a U21-focused tournament since the U20 Asian Cup is already doing its job. In fact, the quality of the U20 Asian Cup is also getting higher thanks to the quality of players being produced and developed by most Asian nations. The last iteration of the U20 Asian Cup was a good glimpse into what teams could do before they headed off to the U20 World Cup later last year, and I think it should stay that way, as a good practice and competitive environment for Asian teams to get used to before they compete at the worldwide stage.

So, while this tournament is still a good competitive environment where young players can test themselves against their peers from across the continent, where does that leave the U23 Asian Cup in the grand scheme of things?

Considering how much first team football most U23 players are getting at the moment, and the fact that the average age of the tournament is about 21 years old, it might be best to switch to being a quadrennial tournament (or happens every 4 years). This can actually raises the stake for the tournament as it can provide a platform for some players to be called up to the first team for the next Asian Cup. Teams can also experiment with new tactical ideas that they want to use at the next Asian Cup, which can provide interesting ideas for other Asian coaches to study and follow. Basically, the U23 Asian Cup should become a precursor to the next Asian Cup while also retains its status as Asia’s official qualification pathway to the Summer Olympics, in my opinion.

I actually think I might already be slow to the idea since the AFC commitee has agreed to do exactly that in their meeting way back in 2024! It will be a very positive change given the current landscape of football, which is heading towards being younger and being more global.

But, for now, let’s enjoy the final biennial U23 Asian Cup as it heads into the knockout phase!

Nice work! Keep it up 👍